Fire Departments

This was originally written for and published on a different website (“Ask an Anarchist”) which has now been incorporated into the NAC site. The views expressed are just one person’s opinion and may not represent what people in NAC believe now. This post was written by Z.

Lois asks:

“If there was a fire, would anarchists call the fire department?”

Yes. I can’t think of any reason why an Anarchist wouldn’t call the fire department.

Fire Departments are actually a good service that exist solely to help people and communities. They save people, put out fires, and stop fires from spreading. It’s a social service that everyone benefits from.

In an anarchist society, there would probably be a volunteer firefighter system, or maybe even fire departments in larger cities. It makes sense for there to be specially trained people to deal with fires.

The police are completely different and will be discussed in a future post.

Alternate answer from A.K. Applegate:

Absolutely! Unless we’re the ones who started it, of course.

When it comes to matters of life and death, insisting on some sort of authenticity by refusing to enlist the state’s help would be foolish. Consider yourself lucky to live under a state that at least gives away some crumbs in the form of public services as your compensation for submitting to their exploitation.

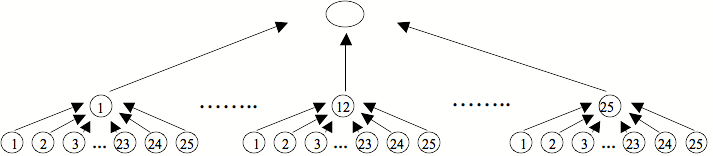

That aside, a fire department is an extension of the principle of solidarity, but for a social organization as large as a city. Since time immemorial, neighbors have always helped each other out in emergencies, including fires. I see no reason why a stateless society wouldn’t have them. Anarchists are not opposed to organized civilization (well, anarcho-primitivists are, but that’s another question), and fire departments are necessary for organized civilization. And really, fire departments are probably one of the easier problems to solve in a stateless society. They would work basically the same as they do now, except instead of being funded via coercive taxation, the needs of the firefighters, like the needs of all workers, would be provided via a system of free distribution. People would choose jobs that interest them, and some people are interested in being firefighters.

But I think this question gets at a matter a lot of people are concerned about when it comes to anarchism. People need social services that governments usually provide, like roads and fire departments. But it’s only because of an arbitrary distinction that is a result of capitalist ideology that we look at the state-provided social services as being any different than market-provided social services. We need roads and fire departments, but we also need food, shelter, healthcare, and energy. There’s no reason to conceptually split these goods into goods that the state provides and goods that the market provides; they’re just goods. And as anarchists, we want all goods to be provided free to all. Civilization, in order to function, needs many state employees just as it needs many private sector employees, but it needs neither the state nor capitalism to provide these employees. Every worker (and “worker” includes the unemployed and the retired) is a part of society, we all provide something that society needs in order to operate. We need firefighters to fight the fires just like we need people to pick the crops, care for the children, scrub the toilets, heal the sick, wash the clothes, build the houses. These are all things that we, as humans, are intrinsically motivated to provide for ourselves, and therefore each other, because these things can often only be acquired through collective action and the division of labor. We want to live well, and care for one another. What we don’t need (nor should we want) are states or the capitalist class employing coercive systems like private property and taxation to get in the way, and insert themselves needlessly into the equation so they can run the system for their benefit at the expense of everyone else.